Empathy VS Sympathy: The Importance of an Endangered Virtue

Empathy underlies virtually everything that makes society work—like trust, altruism, collaboration, love, charity. Failure to empathize is a key part of most social problems—crime, violence, war, racism, child abuse, and inequity, to name just a few.

-Bruce D. Perry

According to psychologists Daniel Goleman and Paul Ekman, empathy can be categorized in three ways:

Cognitive empathy is understanding what another might be thinking. It is recognizing the feelings of others and processing their emotions.

Emotional empathy allows you to feel the same emotion as another. This affective empathy builds emotional connections with others.

Compassionate empathy is the subsequent action following the shared emotion. This is the empathic concern that enables us to help another person.

These three types all interact when we practice empathy. I once had a student who confided in me of a terrible injustice she suffered. I recognized cognitively what that feels like, reflecting on my own experiences of perceived injustice. I felt her burden and was compelled to support her in finding resources and healing.

This sophisticated skill is not to be confused with sympathy. As Neel Burton describes:

Sympathy (‘fellow feeling’, ‘community of feeling’) is a feeling of care and concern for someone, often someone close, accompanied by a wish to see him better off or happier. …However, sympathy, unlike empathy, does not involve a shared perspective or shared emotions, and while the facial expressions of sympathy do convey caring and concern, they do not convey shared distress.

Is Empathy on the Decline?

In an infamous clip from Fox News, Corey Lewandowski responded to the report of a 10-year-old girl with Down Syndrome who was separated from her mother at the US-Mexico border with a controversial and sarcastic “Womp, womp.” Unfortunately, Lewandowski’s apathetic response to another’s genuine hurt is not unique. Media is bursting with stories of politicians brazenly disregarding the pain of the “other.” Popular documentary series detail the callousness of sociopaths and serial killers. Newspapers report perpetrators of hate crimes whose actions tear communities apart. An inability to take another’s perspective and relate to his or her emotional experiences seems to be at the heart of each of these events.

Current trends that reveal our society’s increasing inability to empathize have researchers worried about where western culture is headed. As Bruce Perry, author of Born for Love: Why Empathy Is Essential–and Endangered, explains:

Failure to understand and cultivate empathy, however, could lead to a society in which no one would want to live—a cold, violent, chaotic, and terrifying war of all against all. This destructive type of culture has appeared repeatedly in various times and places in human history and still reigns in some parts of the world. And it’s a culture that we could be inadvertently developing throughout America if we do not address current trends in child rearing, education, economic inequality, and our core values.

The “terrifying war of all against all” that Perry describes seems to be nearing. According to the State of the Heart 2016 report, emotional intelligence is on the decline.

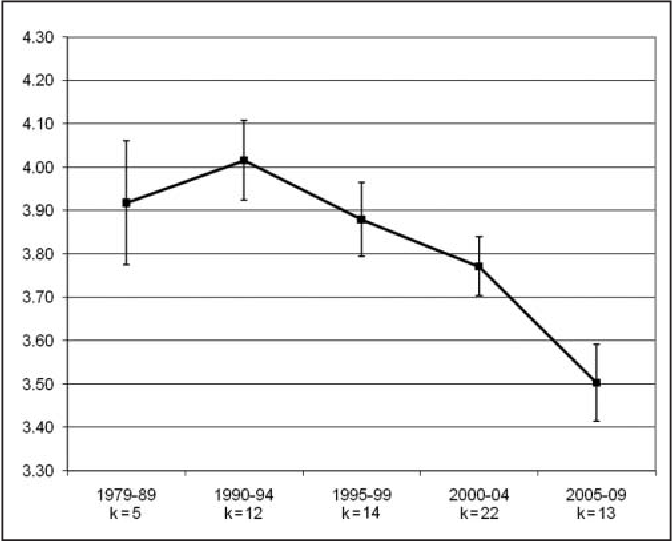

Researcher Sara Konrath studied empathy for decades, testing young people’s agreement with statements such as: “It’s not really my problem if others are in trouble and need help” or “Before criticizing somebody I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place.” She found this endangered trait is on the decline. More students say it’s not their problem to help people in trouble, not their job to see the world from someone else’s perspective.

Graph taken from here

College students’ Empathic Concern scores by period Note: Capped vertical bars denote 1 SE.

The Importance of Empathy

The root of morality is found in empathy since it is the shared pain of others that moves one toward compassion. Empathy is associated with a host of positive outcomes including improved relationship satisfaction between romantic partners and increased levels of trust between patients and physicians. It is also a precursor for prosocial behavior.

The lack thereof has been associated with bullying, aggression, and criminality, and it allows offenders to rationalize their behavior. Daniel Goleman gave examples of such justification:

For rapists, the lies include, “Women really want to be raped,” or “If she resists, she’s just playing hard to get.” For molesters, it’s, “I’m not hurting the child, just showing love,” or “This is just another form of affection.” For physically abusive parents, “This is just good discipline.”

What aided my own ability to take my student’s perspective? Was I one of the lucky ones, innate with some kind of compassion gene?

There is no dichotomy between those who were born to have empathy and those who weren’t. As Brené Brown said, “We are hardwired to connect with others, it’s what gives purpose and meaning to our lives, and without it there is suffering.”

Often people who lack empathy had troubled histories, indicating the significance of children learning this crucial skill at a young age. As research explodes on what empathy is and why it’s important, so does an inquiry on how to teach it.

There is no greater time than now to cultivate empathy in the rising generation, a skill crucial for future effective leadership in a polarized cultural climate.